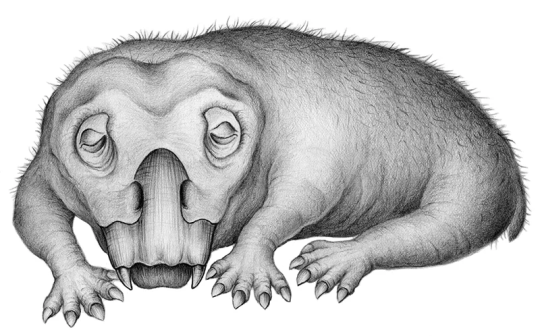

Researchers analyzing 250-year-old fossils found evidence that this pig-sized mammal relation, a genus called Lystrosaurus, hibernated. Normally fossils don’t tell us much about metabolism rate shifts that are evidence of hibernation. But the Lystrosaurus has tusks that grow continuously. Like tree rings, the tusks give a record of the animal’s activity.

A comparison of cross-sections of tusks from six Antarctic Lystrosaurus and cross-sections of tusks from four Lystrosaurus from South Africa showed periods of less growth and greater stress that were exclusive to the Antarctica samples. The distinct periods match up with what modern hibernating animals go through today. It also matches where the animals lived: living in Antarctica, hibernation makes sense as a way to handle extreme seasonal weather. Turns out hibernation is a very, very old adaptation